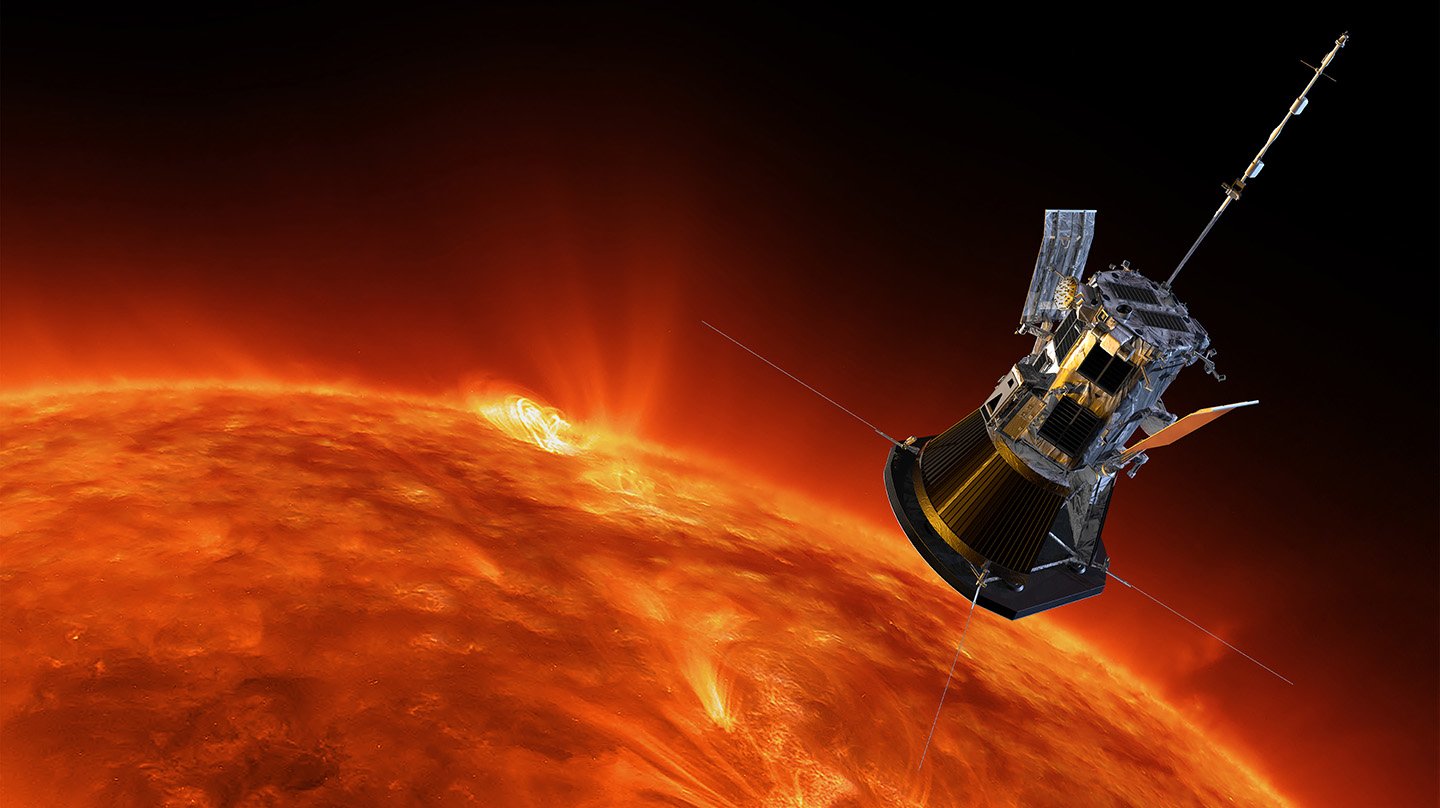

The short answer is: NASA didn’t “touch” the Sun in the sense of landing on it, but its Parker Solar Probe did penetrate the Sun’s outer atmosphere (the corona). This is often described as “touching the Sun.” Here’s how that works, with details:

What it means to “touch the Sun”

- The Sun isn’t a solid surface you can land on. It’s a massive ball of plasma and gas (mostly hydrogen and helium).

- Around the Sun is an atmosphere of charged particles called the corona. Even though this is very hot (millions of degrees), it is extremely tenuous (very low density).

- When NASA says the probe “touched the Sun,” they mean it entered or flew through this outer atmospheric region, sampling particles, magnetic fields, and solar winds in situ (i.e. directly). NASA Science+2NASA Science+2

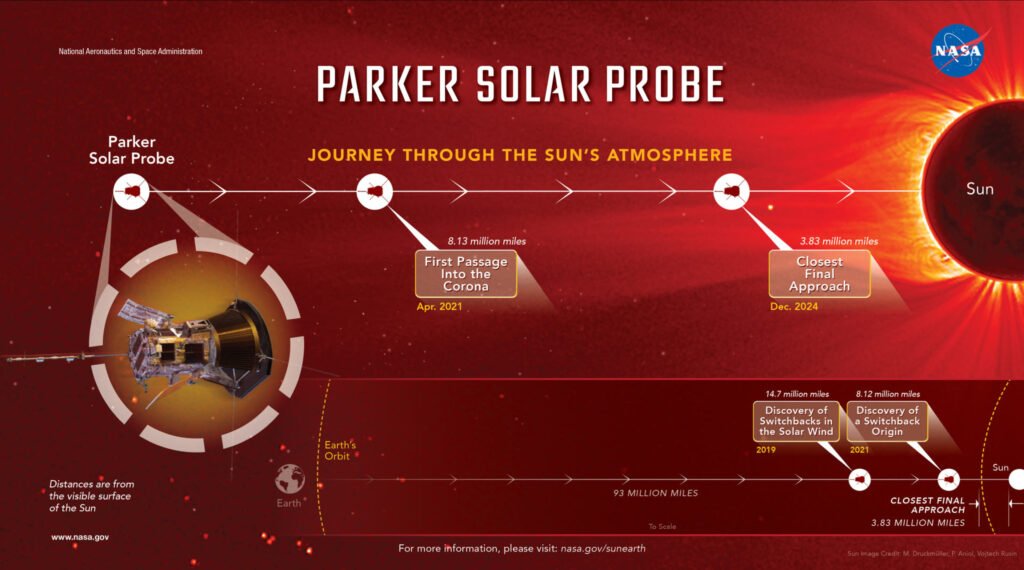

- In December 2021, data showed that Parker Solar Probe had indeed passed through the corona for the first time — marking the first time a spacecraft “touched” the Sun’s atmosphere. Space+3NASA+3NASA Science+3

How the Parker Solar Probe does it — the engineering trick

Getting a spacecraft so close to the Sun is extremely difficult, because of intense heat, radiation, and solar particle bombardment. Here’s how Parker is designed to survive and operate:

1. Orbit and trajectory

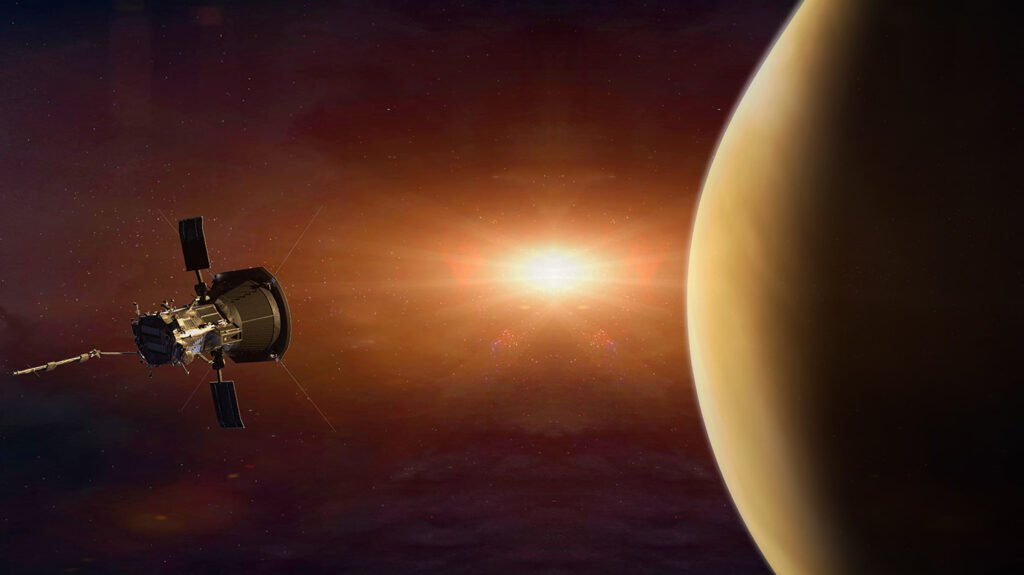

- It uses multiple gravity assists (from Venus) to gradually change its orbit, allowing it to come ever closer to the Sun. Wikipedia+2NASA Science+2

- Its orbit is highly elliptical (i.e. elongated) — so it approaches close to the Sun (perihelion), then moves away, repeating many times. Wikipedia+2NASA Science+2

2. Heat protection (Thermal Protection System)

- The probe has a heat shield (also called the Thermal Protection System, or TPS) facing the Sun. This shield is made from a carbon‐composite sandwich (carbon panels with a foam core) and is roughly 4.5 inches (about 11.4 cm) thick. Wikipedia+2NASA Science+2

- The sun-facing side has a reflective coating to minimize absorption of solar energy. Wikipedia+1

- Behind the shield, the instruments and spacecraft body remain in the “shadow” of that shield, keeping their temperature in a safe range (around 27 °C or so). Wikipedia+2NASA Science+2

3. Autonomy and attitude control

- Because the spacecraft is sometimes out of communication due to its proximity to the Sun, it must autonomously detect if sunlight is encroaching on its protected areas (i.e. creeping past the shield margin). It uses light sensors to detect stray sunlight. Wikipedia+1

- If necessary, it adjusts its orientation using reaction wheels so that the shield remains between the Sun and the rest of the spacecraft. Wikipedia+1

4. Solar panels and cooling

- The probe normally uses a larger solar panel array when farther from the Sun, but during close approaches that large panel is retracted behind the heat shield. A smaller secondary array is used during perihelion. Wikipedia+1

- That smaller array has pumped-fluid cooling systems to keep it from overheating. Wikipedia+1

Milestones & record approaches

- In 2021, Parker Solar Probe made its first confirmed pass through the Sun’s corona. That was the first “touch” in historical terms. SciTechDaily+3NASA Science+3NASA+3

- On December 24, 2024, it set a new record for closeness, coming within 3.8 million miles (≈ 6.1 million km) of the Sun’s surface. NASA Science+3NASA Science+3Wikipedia+3

- At that closest approach, Parker reached a speed of ~ 430,000 miles per hour (~191 km/s), making it the fastest human-made object. NASA Science+3NASA Science+3Wikipedia+3

- After passing perihelion, the spacecraft was confirmed to be in “good health” and transmitting data back. NASA Science+2NASASpaceFlight.com+2

What was learned, and why it matters

By “touching” the Sun’s atmosphere, Parker is able to:

- Directly sample the plasma (ionized gas), magnetic fields, and energetic particles in the corona.

- Investigate why the solar corona is much hotter (millions of degrees) than the Sun’s visible surface (only ~5,500 °C or ~10,000 °F).

- Study how the solar wind (a stream of charged particles from the Sun) is accelerated and evolves.

- Help predict space weather, which affects Earth — satellites, power grids, communications, etc.

Image Credit: NASA / Johns Hopkins APL